Green Infrastructure Takes Off Across Asia-Pacific

Highlights

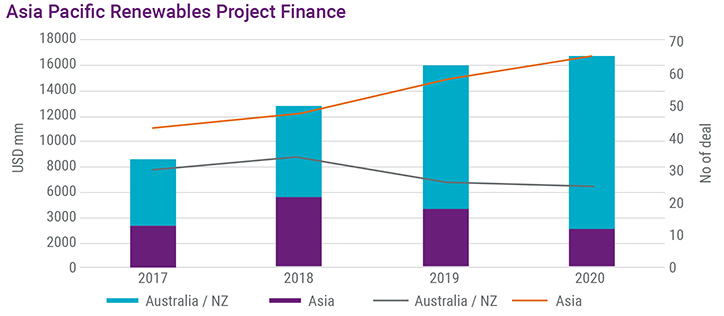

- Asian renewables project finance has grown from $5.3 billion in 2017 to around $13.7 billion by 2020. Asia’s energy demands and renewables policies point to further significant increases in greenfield renewables project finance. Asia-Pacific’s share of the total project finance market will also grow as a result.

- Some global infrastructure debt mandates now seek a 50%-plus allocation to Asia-Pacific assets. The risk-return profile is not necessarily different from western markets, but the proliferation of deals in Asia-Pacific offers investors huge diversification potential.

- Infrastructure debt is a powerful vehicle for ESG activities because it focuses on a single asset, allowing for the collection of accurate and relevant ESG information. Like other fixed-income assets, infrastructure debt can be accompanied by a green label.

Less well known is the shift currently going on within the asset class. Until recently, the focus of investors in infrastructure debt was largely on the US and Europe and, to some extent, on Australia. That focus is starting to shift to include Asia, driven in no small part by increased activity across the region in ESG-related infrastructure debt.

“The Asian renewables market has really taken off,” says Angus Davidson, managing director of APAC infrastructure at Natixis Investment Managers (Natixis IM). “Given the energy needs of the region, there is a tremendous amount of growth still to come. This gives infrastructure debt investors a great opportunity to diversify their portfolios.”

The Rest of Asia Fast Catching Up With Australia

ESG-related infrastructure has long been a feature of the Australian investment landscape, initially driven by renewables development stemming from Federal and State Government policies. Today, Australia is among the most active global markets in renewables investment and finance. More recently, ESG financing has also been adopted across other sectors, such as telecommunications and transport, via green and sustainability-linked project loans.

In the last few years, the growth in ESG-related infrastructure debt elsewhere in Asia-Pacific has been driven by a surge of activity in renewables, particularly in India, Taiwan and Japan. Taiwan, for example, went from relatively little project finance in 2016 to nearly $9 billion in project debt provided to four offshore windfarms between 2018-2020.

In 2021, there have been significant transactions in rooftop solar in China, floating solar in Indonesia, and one of the largest green bonds coming out of India. One of the largest solar markets in the region, Vietnam, has also seen an uptick in international lending activity. Renewable energy made up more than half of the deals in Asia-Pacific in the first half of 2021. “The growth in renewables is remarkable,” says Davidson. “Nearly every infrastructure debt investor in Asia is looking for a mandate that has an ESG focus, and the supply is coming on to meet this demand.”

Asian Governments Set Ambitious Targets

The supply of ESG-focused infrastructure is partly due to investor demand and partly to meet the edict of Asia-Pacific policymakers.

The energy demands of the region are immense. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) predicts south-east Asian energy consumption will double by 2040. The Asia-Pacific region has historically relied on coal-fired power generation, but environmental concerns mean the onus of new and replacement power generation will be on renewables.

Most governments in the region are implementing policies that will make their energy supplies more sustainable, with many targeting significant short- to medium-term additions. For example, India has announced a target of 450MW in renewables by 2030 – they are currently at 100GW. Indonesia, one of five Asian countries with stated net zero targets, is planning to install 20GW of new-build renewables by 2030. Three of the others – China, Japan and Korea – are looking at offshore wind as a solution. China installed over 50% of the world’s new offshore wind in 2020 (3GW), whereas Japan and Korea are targeting 12GW of offshore wind by 2030.

The focus on offshore wind in Asia is notable, given that the cost/GW is significant. For example, just under 2GW of offshore wind in Taiwan has resulted in nearly $9bn in project debt. Projected additions in Taiwan, Japan, Korea, China and Vietnam suggest over 30GW of offshore wind coming to market in the next 10 years.

“A lot of these Asian markets still offer long-term offtake, or Feed-in Tariff (FiT), schemes with government entities, so as an infrastructure debt investor it’s an attractive asset with great underlying rationale,” says Davidson.

Australia, which was at the forefront of the surge in renewables, will also likely see a resurgence in activity as well, driven by upcoming State auctions and infrastructure roadmaps, particularly in Victoria and New South Wales.

Evolution of Asian ESG Infrastructure is a Diversification Opportunity

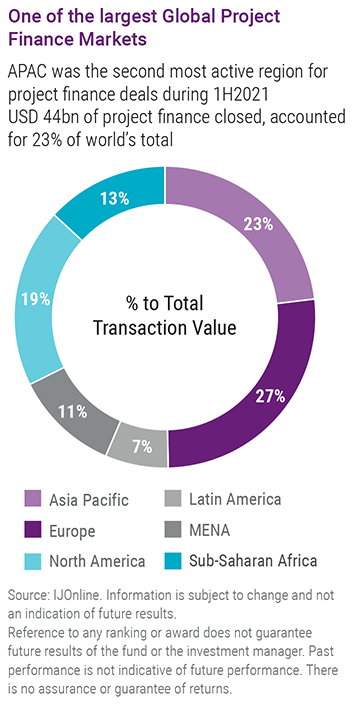

In the first half of 2021, Asia-Pacific infrastructure debt represented almost a quarter of the value of deals done worldwide. Given the surge in ESG-related infrastructure deals this is expected to grow.

The increasing depth and breadth of the Asia-Pacific infrastructure market is leading more investors to seek Asia-Pacific specific infrastructure debt mandates. “Some requests for global infrastructure debt mandates are asking for Asia-Pacific to be 50% or more of the assets now,” notes Davidson. “Properly structured, the risk-return profile is not necessarily different from western markets, but the proliferation of ESG friendly deals in Asia, and the continuation of Australia’s strong pipeline offers investors huge diversification potential.”

The range of assets allows investors to choose from a range of risk-return profiles and a variety of instruments including senior debt, mezzanine debt and equity. An infrastructure senior debt strategy is expected to significantly outperform the corporate bond market index, and the risk characteristics tend to be better than bonds since the yield is secured. A mezzanine strategy has an even higher risk-return profile.

“We can respond to most types of investment criteria, whether that be specific sectors, specific countries, the amount of yield required or the ESG profile,” says Davidson.

The asset class is particularly attractive to investors with longer-term outlooks and liabilities. Insurance companies, for one, are often unable to match very long-term liabilities through traditional bond markets, so are drawn to infrastructure debt where contracts can exceed 20 or even 25 years. In countries which are looking to mirror the EU in applying a capital charge to assets, infrastructure debt is appealing in that it may increasingly receive favourable treatment from many Asian regulators.

Infrastructure Debt and ESG are Natural Bedfellows

Infrastructure debt is a good place to be for investors seeking ESG-focused assets.

Infrastructure debt is a powerful vehicle for ESG because it is focused on a single asset, allowing for the collection of accurate and relevant ESG information. This contrasts with ESG due diligence on corporates, which can be more challenging due to the sheer range and number of corporate activities and the difficulty of clearly identifying and measuring impacts.

The infrastructure debt market has a long history of ESG risk mitigation. For over 15 years, many infrastructure debt lenders have applied International Finance Corporation (IFC) performance standards on social and environmental sustainability, and World Bank Group environmental, health, and safety guidelines, via The Equator Principles risk management framework. Set up in 2003 by four banks, there are now 125 financial institution signatories. “Each time one of those signatories does a deal, it involves highly-specific and accurate ESG-related due diligence which is discrete and signed off by third parties,” Davidson notes.

However, like other assets, infrastructure debt funds or mandates can, where required, also be accompanied by a green label. A label allows pension funds, insurers and other institutional investors to demonstrate to their clients and stakeholders that ESG is at the heart of their processes.

Natixis IM is a signatory to the Principles of Responsible Investment (UNPRI), and in Europe, Natixis IM increasingly adheres to the French GreenFin label for one of its its infrastructure debt funds. In Asia, labels are less prevalent, although many jurisdictions are increasingly requiring considerable ESG transparency in funds marketing themselves as ESG-focused. “This is where our European experience helps us,” says Davidson. “For example, we’ve developed in-house tools to measure project specific carbon eviction for our labels in Europe, that we can easily apply to funds and mandates across Asia-Pacific.”

A Deep Well of Primary Sources

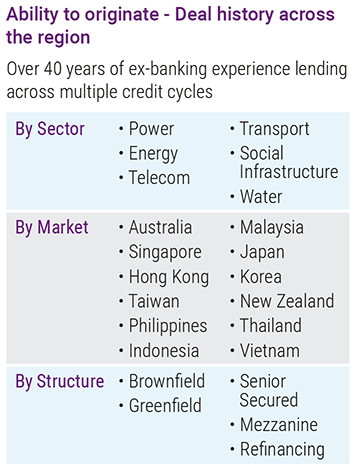

While infrastructure debt often works the same way the world over, local knowledge and contacts are important for sourcing deals. “We’ve been in the region for over 20 years, so we know the landscape and the players,” says Davidson.

Natixis IM’s deal experience spans most Asia-Pacific countries, from the Tier One markets of Australia, Japan and Korea, to Tier Two markets, including Vietnam and Indonesia.

Natixis IM employees have completed deals across Asia in all the major infrastructure sectors and have executed transactions with structures ranging from brownfield to greenfield, and from senior debt to mezzanine.

As a result, Natixis IM is able to leverage a well-developed network in the region, including borrowers, financial advisers, banks, and other institutional lenders. Notably, Natixis IM also manages a co-lending programme with Natixis CIB, its affiliated corporate and investment bank, which provides additional insight and reach into the market.

Finding a Niche

The supply of deals may be rising in Asia, but there is stiff competition. “It’s still a market largely dominated by banks in Asia-Pacific,” says Davidson. “They have the legacy branches, licences, and relationships to efficiently operate around the region.” But, increasingly, the region’s borrowers are considering alternative lenders, and banks are shaping to arrange loan or bonds with institutional investors in mind.

“We are looking to play to the strengths of our clients in sourcing opportunities,” says Davidson. “For that reason we offer long tenors, to match our clients’ long term liabilities, and local currency tranches where our clients have local regional books.”

Opportunities present themselves across the Asia -Pacific region in instances where banks are looking for extra tenor, liquidity for very large transactions or where local bank markets are occasionally experiencing difficulties.

“Institutional lenders have their own requirements, often in terms of yield, and for that reason we try to operate in the primary market and try to do deals where we have market power,” says Davidson.

Better returns for deals can be achieved by getting involved in a transaction from its inception and thereby having a say over the terms and conditions, as well as earning arrangement fees.

Other ways of achieving better pricing are by operating in the smaller deals space, where banks don’t think it financially worthwhile to inhabit. For institutions looking for diversification across a limited infrastructure debt allocation, these types of transactions, properly structured, can be attractive.

Risk can be Managed by Experience and Deep Resources

Infrastructure debt is fairly resilient to economic cycles given that many transactions benefit from long-term revenue contracts underpinning their cashflow projections. This reduces the cyclical traffic risk from, say, a toll road or bridge, or from aircraft traffic fluctuations.

There are potential downside risks, however. These include strong government incentives which can lead to an oversupply of assets, such as occurred in the renewable energy sectors in Australia, Vietnam and China in recent years, causing grid congestion issues. Some projects, such as offshore wind, also present construction risk.

There are market risks too: the growing prevalence of rooftop solar panels, for example, can reduce the demand for power from grids in some markets. This is particularly the case where there is no fixed-rate contract and therefore merchant risk. In fact, particularly in Australia, infrastructure debt providers are being asked to shoulder more merchant risk, increasing the need for information on variables from market reports and in-depth pricing analysis.

All these risks can be mitigated by deep resources, experienced teams and the network to execute sustainable infrastructure debt deals in Asia. “Armed with these resources, returns can be considerably above the yields available on government and blue-chip bonds, at comparable risk levels,” Davidson adds.

Natixis Investment Managers International

French Public Limited liability company with board of Directors (Société Anonyme).

Share capital : €51 371 060,28. RCS Paris : 329 450 738.

Regulated by the Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF) under no. GP 90-009. 43 avenue Pierre Mendès France 75013 Paris.

www.im.natixis.com

Natixis Investment Managers

RCS Paris 453 952 681

Share Capital: €178 251 690

43 avenue Pierre Mendès France

75013 Paris

www.im.natixis.com

This communication is for information only and is intended for investment service providers or other Professional Clients. The analyses and opinions referenced herein represent the subjective views of the author as referenced unless stated otherwise and are subject to change. There can be no assurance that developments will transpire as may be forecasted in this material.

Copyright © 2021 Natixis Investment Managers S.A. – All rights reserved

Infrastructure: the Rise of an Asset Class

Infrastructure: the Rise of an Asset Class

Secure Income and Green Infrastructure: An Unlikely Marriage?

Secure Income and Green Infrastructure: An Unlikely Marriage?